School Age Futures

Bringing visions of a system of school aged childcare in Scotland to life

CLIENT

Scottish Government

YEAR

2024

DELIVERABLE

Storytelling artefacts to ground and communicate a programme vision

Bringing visions of a system of school aged childcare in Scotland to life

CLIENT

Scottish Government

YEAR

2024

DELIVERABLE

Storytelling artefacts to ground and communicate a programme vision

The School Age Childcare (SACC) team at the Scottish Government had a vision for their policy but it was too high-level to show how day-to-day life might change for families. This made it hard to define what support the Government aimed to offer, or how the SACC team should move forward. The team needed to add depth to their vision and explore what it might feel like in practice. Through this we hoped to build a shared understanding of the vision in their policy unit, translate ideas into tools and artefacts that could help communicate the vision to stakeholders.

The Scottish Government is the devolved government for Scotland. It is responsible for running the country’s day-to-day affairs and delivering public services in areas that are devolved from the UK Government.

To move towards action, the project needed a structured way to explore complexity, build internal consensus, and make future possibilities tangible. We designed a three-phase approach that brought together policy expertise, design research, and speculative thinking. While this was linear in our planning, its execution was more of a layered exploration—helping the team uncover tensions, explore strategic futures, and align around shared priorities.

Phase 1: Immersion

We reviewed two years of research, pilots, and community engagement, alongside interviews and workshops with stakeholders. A key result of this was the identification of what we called ‘tensions’ that were sitting in the team. They weren’t complete blockers but they held central questions the team was grappling with such as the role of government (is it a childcare provider or an enabler?) and how much the programme should focus on putting out fires in the existing system versus building something new from the ground up.

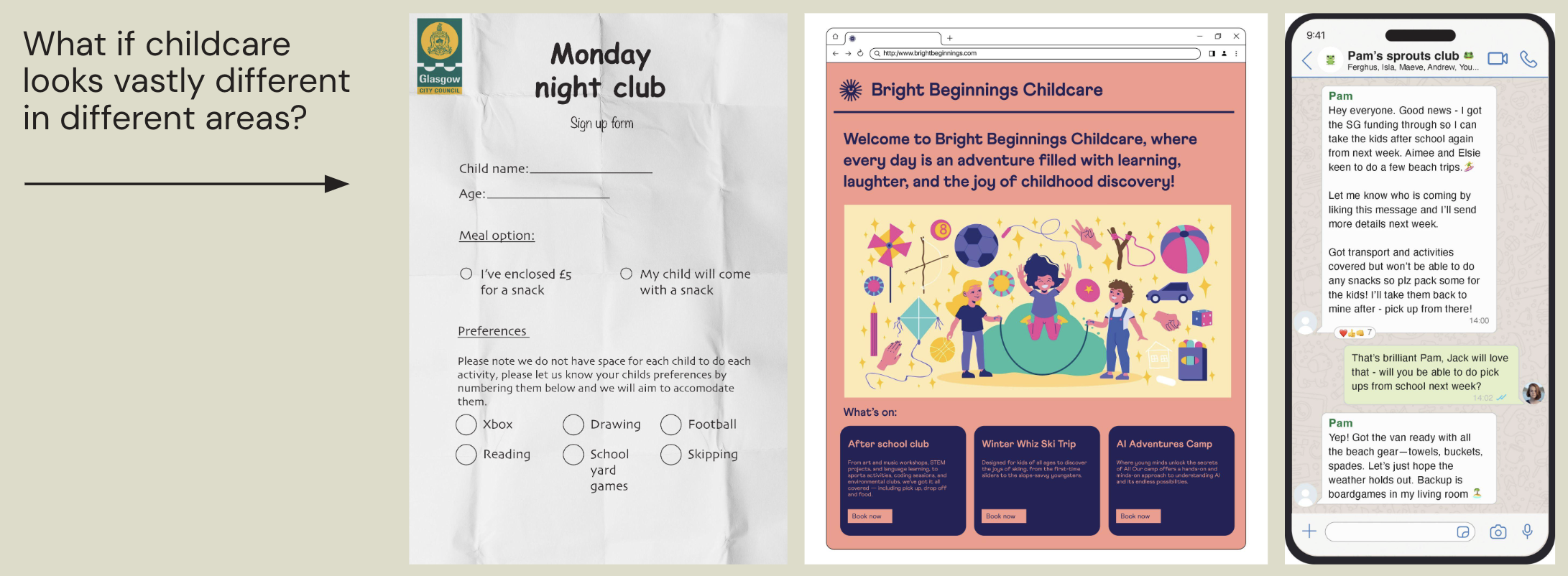

Phase 2: World-building

Using the tensions as stimulus, we developed speculative scenarios amplifying these tensions into provocative futures (e.g., a gig-economy childcare, layered benefits that obfuscated eligibility, or unequal services across different geographies). Through fictional artefacts like social media posts, WhatsApp chats, and prototyped app experiences, we made futures tangible and used workshops to spark reactions, surface assumptions, and identify trade-offs. These workshops ended in consensus around what a 2- and 10-year vision of the programme would look like.

Phase 3: Visioning

In the final phase, we crafted stories - ‘vignettes’ - that drew on the ideas underpinning the short- and long-term visions developed in the workshop. By connecting these with the programme’s strategic priorities and building on previous work (i.e. programme user needs), we created artefacts that helped tell the story of the programme and its intentions. These artefacts aligned teams, clarified values, and built momentum for future delivery.

Bringing the vision to life

The 2- and 10-year future visions developed during the project became internal reference points and are now used to communicate programme direction to ministers, stakeholders, and delivery partners. While not firm commitments, they illustrate what changes in policy might result in for people’s everyday experience.

Creating alignment to support strategic planning

The surfacing of tensions and participatory process of visioning helped strengthen alignment across the team. This was of particular importance as the programme moved into space for more confident strategic planning and prioritisation across workstreams.

Supporting the evolution of policy pilots

The storytelling and provotypes helped the team frame how existing tests of change could evolve into a broader national offer. This storytelling has helped anchor policy discussions around real human impacts.

Central to our approach was the use of provotypes - speculative artefacts or prototypes designed to provoke and stimulate reaction. Sometimes, when working with abstract and intangible ideas, bringing a potential future to life becomes a much more powerful facilitator of discussion than complex descriptions. These artefacts are often able to speak to complicated ideas, that might be second- or third-order consequences of a policy decision. For instance, what would happen if a place-based approach created very different levels of service in different geographical locations? What level of inequality would be acceptable, if any? And how could you modify your policy to mitigate these inequalities? Sometimes, putting something on a piece of paper cuts through all the noise and lets people quickly get to the centre of a discussion.